Equal opportunities to perform – do we have room for improvement?

Despite Norway being one of the world's most gender-equal countries in the world (1), we have significantly fewer female medals and participants in sports. However, cross-country skiing is one of the sports where Norway has achieved many medals also for women, for some periods even more than men. Recent analyses also show that the women’s cross-country skiing competitions attract far more international TV viewers than men (2). However, the female participation rate is significantly lower, and the cross-country skiing arena, including coaches, leaders, and support staff, remains heavily male-dominated. What can we do differently to encourage more female skiers to pursue their dreams, unleash their potential, and choose to stay in the sport after their careers?

In a recent study (3), Norwegian endurance coaches at the elite level reported that they primarily used an individual approach in their coaching, adapting training based on individual differences rather than gender. However, a thought-provoking finding, was that all coaches talked about the male athlete as the norm. If the development of training philosophies and equipment are based on what works best for men, this could be two of several limiting factors for training adaptation, participation, and development of female athletes.

One challenge is that there is significantly less research conducted on female athletes compared to male athletes, and almost no research on female Paralympic athletes. The scientific basis is therefore much weaker on the women's side, and it also seems like the existing knowledge is not communicated well enough to coaches and athletes. In this article, we discuss gender differences in training and performance, highlighting important areas in the development process of female cross-country skiers. The goal of the discussion is to both increase the number of participants in sports (throughout life) and improve performance. A more gender-equal sport where more athletes participate and get the opportunity to reach their potential, benefits all!

Differences in physiology and the demands of the sport

Until puberty, boys and girls undergo almost identical physical development. During puberty, girls begin to produce estrogen and progesterone, leading to changes in body composition with a higher proportion of fat relative to muscle mass. In contrast, boys produce more testosterone, contributing to the development of a larger body with more muscle mass, especially in the upper body, as well as a higher concentration of hemoglobin in their blood. These factors are also the main reasons why men achieve higher speeds than women in endurance sports (4). Other relevant physiological differences include the fact that women must train and perform according to their menstrual cycle, possible use of hormonal contraception, and the potential for pregnancy during their careers.

The training content is primarily based on the demands of the sport. In the World Cup, World Championships, and the Olympics, there has long been a clear gender difference with shorter distances for female vs. male athletes. While competition duration in sprint events has been similar (~3 minutes), female athletes until the 2022/23 season have had significantly shorter competition duration in long-distance cross-country skiing (25-80 minutes vs. 35-125 minutes). Comparisons of average speeds (top 3 in the World Cup) show that men go about 10-12% faster than women in sprint and individual start (10/15 km), while smaller differences (7-8%) are observed in skiathlon (15/30 km) and long-distance races (30/50 km). With the introduction of equal distances in the World Cup from the 2022/23 season, this has changed so that female cross-country skiers now have 13-15% longer competition duration and achieve 12-16% lower average speeds than men, regardless of distance (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Gender differences in competition duration and average speed for the 2018 and 2023 seasons (calculations are based on the top 3 in World Cup races).

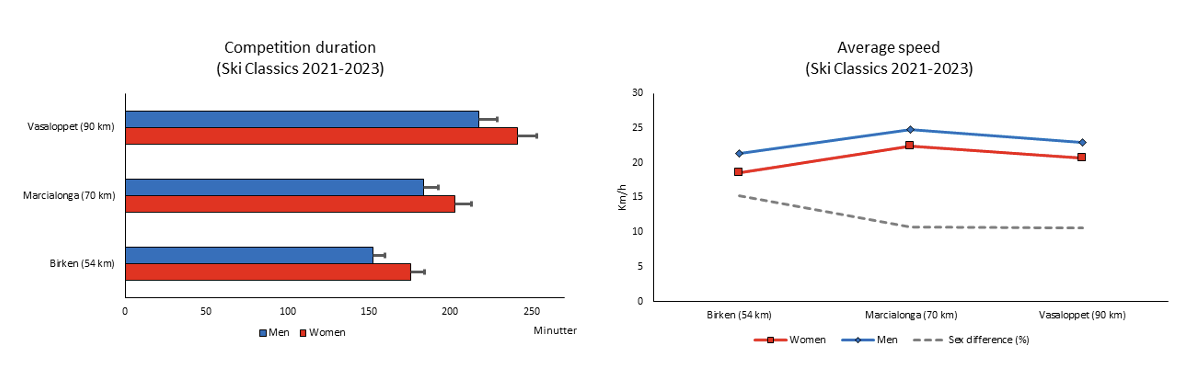

In Ski Classics, men and women have competed over similar distances for a long time, leading to 10-15% longer competition duration for the women. Gender differences in average speed seem to be somewhat smaller in Marcialonga and Vasaloppet (10%), than in Birken (15%, see Figure 2). The reason for this is likely the relatively flat terrain profiles, leading to higher speed and large pelotons resulting in smaller gender differences in Marcialonga and Vasaloppet, while the longer uphill sections in Birken lead to greater gender differences, as also observed in other analyses (5).

Figure 2: Competition duration and average speed for three Ski Classics races (calculations for the top 3 from 2021-2023)

Should Women Train Differently Than Men?

An interesting question is whether the gender differences in demands and physiology have any consequences on how training should be planned and executed for male and female cross-country skiers. Overall, there is no scientific evidence suggesting that women achieve less training adaptations than men when performing the same relative training load, of strength or endurance training. However, there are factors that we believe it is important to be aware of.

Endurance Training

In the previous article, we focused on the fact that many athletes train too hard to realize their potential, emphasizing the importance of intensity control and training with high technical quality in all intensity zones. There is no research supporting that women should use different intensity zones than men. However, the speed range within the different intensity zones may be somewhat narrower in female athletes due to lower aerobic capacity. During and after puberty, the bodily changes can also lead to alterations in the relationship between heart rate, ventilation, and muscular load. It may therefore be particularly important to encourage female athletes to control training based on perceived exertion and muscular load (6).

Some studies have also shown that when women and men were instructed to train at low intensity, female athletes trained at significantly higher heart rates and lactate levels than their male counterparts (7, 8). It is unclear whether this was because female skiers tried to keep up with the males, to “please” the coach, or if women were forced to train at higher intensity to ski technically correct in the uphill sections. Female athletes also ski at a slightly lower speed than men at the same level, thus using more of the sub-techniques (diagonal and gear-2), loading the legs more than double poling and gear-3.

An example of this is data from a session in Holmenkollen for two athletes in Team Aker Dæhlie (see Figure 3). The athletes performed the same session, used the same roller skis (IDT 2), and measured nearly the same lactate levels after completing the lap (2.1 vs. 2.4 mmol/L). Nevertheless, we observed clear differences in the use of sub-techniques.

Figure 3: Data from Archinisis (GPS) in Holmenkollen showing differences in the use of various sub-techniques for women and men.

Our experience at the senior level (>25 years) is that women respond just as well to training and, in many cases, tolerate higher training loads than men. Therefore, we think that in general, it is more important to individualize the training for each athlete rather than making gender-specific adjustments. One strength of cross-country skiing is that girls and boys, women and men, train together in mixed groups from childhood to elite level. Integrated groups where athletes train together are highly valued in Team Aker Dæhlie, including the inclusion of Paralympic athletes.

However, we believe we can become better when it comes to adapting the training for female athletes during junior age, and also during the transition from junior to senior levels. This period requires the ability to use the entire "toolbox" as coaches to better tailor the training to each individual's needs. This includes training organization, use of different session designs (threshold sessions can also be performed as short intervals), terrain, and resistance on roller skis. The bodily changes of female athletes coincide with the time when the sport becomes more serious, and both distances and training volumes increase. Communication with athletes that it is normal to have a period of stagnation during this stage of development (14-20 years) and that this can “hit” each athlete differently is crucial. During periods of limited progress in endurance performance, it is important to help athletes see improvement in other areas (technique, speed, and strength).

Altitude Training

Regarding gender differences in altitude training, a recent literature review (9) highlighted that the respiratory system of women is more negatively affected by altitude exposure, leading to lower blood oxygen saturation and reduced work capacity. However, women have better vascular reactivity than men, resulting in more efficient blood distribution and oxygen uptake in the muscles. Better fat metabolism during altitude training is also linked to more type-I fibers in women. This can be beneficial with large amounts of low-intensity training. The negative and positive gender differences with altitude exposure likely cancel each other out. Regarding the increase in hemoglobin mass during altitude training, there is no clear evidence of gender differences, and any potentially smaller altitude response in women is likely due to lower iron levels, which are more common in women. Therefore, monitoring iron status in connection to altitude exposure, is particularly important for female athletes. The effects of different phases of the menstrual cycle and the use of hormonal contraception in combination with altitude training, are currently poorly investigated. In Team Aker Dæhlie, we have conducted altitude training similarly for the male and female athletes, meaning that training is individualized as during lowland training. Our experience is that some athletes tolerate more altitude exposure than others, regardless of gender. This can vary between each altitude camp and also depends on the athlete's physical performance level, health situation, and the training load prior to the camp.

Strength Training

Even though cross-country skiing is an endurance sport, it also requires a certain level of strength to ski with an efficient technique, acceleration and positioning during sprints or mass start races as well as being able to win the final sprint. A recent study (10) investigated gender differences in training progression from junior to world-class level in 17 Norwegian cross-country skiers. The study revealed that the total strength training volume (including general and maximal strength training) was not statistically different during junior age (25 vs. 17 hours), but that the female athletes significantly increased their amount of strength training from junior to world-class level, where they trained almost twice as much strength as their male counterparts (75 vs. 41 hours).

Arguments for why it might be beneficial for female athletes to perform a higher volume of strength training include lower muscle mass than men, especially in the upper body (11). Some female athletes may therefore need to train more strength, both to change their body composition (increase muscle mass) and to reach a sufficient strength level to optimize performance. We also believe it may be beneficial for girls to start strength training before boys in order to be better prepared to tolerate training with a heavier body, due to the natural occurring bodily changes during puberty. Our experience (regardless of gender) is that the development of sufficient strength during youth and junior years creates a better starting point for optimal technique development as seniors.

The female athletes on Team Aker Dæhlie trained between 41 and 95 hours of strength in the 2022/23 season, depending on individual needs. Figure 4 shows strength training data for Astrid Øyre Slind over the past five seasons.

Figure 4: Distribution of strength training (maximal and general) for Astrid Øyre Slind seasons 2018-2023.

Technical Training

An interesting question is whether women can benefit from using different technical strategies than men and hence should emphasize other aspects in training to develop their technique as effectively as possible. There is a lack of research in this area, and it is therefore uncertain whether methods for effective technique development differ between women and men. An important aspect of gender differences in technique is the lower speed and larger proportion of competition time in uphill sections in female athletes compared to male athletes, leading to more use of the diagonal and gear-2 sub-techniques among women compared to men, who use more double pooling and gear-3 (12). These gender differences have been accentuated with the introduction of equal distances. Therefore, it may be useful to spend more time developing techniques (and gears) used at lower speeds in female athletes. Female athletes also stay closer to speed thresholds for transitions between sub-techniques (12, 13). This likely makes it even more important for female skiers to be skilled at "shifting gears" within techniques and mastering efficient transitions between sub-techniques.

Our experience is that the development of technique is complex and highly individual and that the use of sub-techniques does not always differ between the genders. We therefore believe that the most important is to tailor the technical training to each individual, as the technique must be adapted to the physiological prerequisites of each athlete. However, it is probably important not to be stuck in male technical solutions but to use female role models with similar physiological prerequisites in the technical training of different sub-techniques and gearing. Our experience is that it is especially important to stimulate curiosity on technical development in female athletes and inspire them to experiment and play to find their optimal technical solutions — contrary to forcing women to adapt a "male" technical solution..

Pacing strategy

Another crucial factor for performance in cross-country skiing is to distribute energy in the smartest way possible to achieve the best result. Studies from marathon running have shown that women seem to be better at maintaining a more even pacing strategy than men. Faster depletion of glycogen stores, in combination with psychological factors such as higher competition orientation in men versus women, has been suggested as an explanation for this (4, 14).

No gender differences in race strategy have been found in cross-country skiing. However, higher speed and larger groups of skiers lead to a higher drafting effect in the men’s versus the women's races. This is likely one reason why mass starts among female cross-country skiers often break up at an earlier stage and are less frequently decided in the final kilometer than is often the case among male skiers. In Ski Classics, women often ski in smaller groups (1-6 individuals), which can make the physical cost higher than in the men's category, where athletes have a larger opportunity to "hide" in a large group of skiers to save energy. In some races, there is also an extra tactical element for female skiers as they start 15-30 minutes before the men's category. A decisive phase of the race can, therefore, be when the male passes the female athletes. This means that there are some different tactical elements in the female versus male races.

Our experience is that all athletes must plan and perform their races based on a thorough analysis of their strengths and weaknesses. To be able to execute this well, athletes need to be given sufficient learning situations to experiment with tactical solutions, regardless of gender. However, we do notice some differences in the "cynicism" between male and female skiers. Why is it cool when male runners draft 99% of the race and win the final sprint, while it's "unfair" in the women's category? We believe that female athletes should be more encouraged to use their own individual strengths when it comes to selecting the most ideal tactical strategy for each race.

Equipment

Both technique and physiology develop in interaction with equipment. In cross-country skiing, ski, boots, bindings, poles, and clothing are crucial for performance. In football, several recent studies have focused on the development of technology and equipment based on the male body's physiology and prerequisites. For example, most football shoes are developed to fit a male foot. Women's feet have a different structure than men's, and poorly fitted football shoes are considered both performance-decreasing and a cause of increased injury risk for female players (15). Another example is the importance of proper breast support for female athletes. Studies in running have shown up to a 7% reduction in the work economy with inadequate breast support (16). Similar studies do not exist in cross-country skiing, and a relevant question is whether female athletes with different body composition, speed, and use of sub-techniques could perform better if more resources were invested in developing ski equipment based on the female body. The proportion of female waxers and ski testers is also very low, so it is likely that important perspectives in equipment development and optimization of both kick wax, structure, and glide wax are lost. A practical example is the consequence of different ski lengths between women and men. A typical men's ski is often 10 cm longer than a women's ski. This means that men have a longer kick wax zone than women. Sufficient grip depends both on finding the right wax and having sufficient surface area of the ski against the snow. A female athlete with 40 cm2 less area against the snow will naturally get a worse grip. The same would happen if the kickwax zone was reduced by a corresponding area in a male skier.

Our experience is that the solution to this is relatively simple: wax with a product that provides better grip and/or choose slightly softer skis. In an ideal world, female ski testers should test products on relevant ski lengths for female athletes, but the challenge is to crack the code on how to make the service job more attractive to women.

Menstrual Cycle and Hormonal Contraception

A highly relevant topic in sports research is whether the menstrual cycle or the use of hormonal contraception can affect training and/or performance. As shown in Figure 4, the levels of the female sex hormones estrogen and progesterone fluctuate throughout the menstrual cycle and are also affected by the use of hormonal contraception. However, based on current research, there are no general recommendations that can be given at the group level for either performance or training periodization related to the menstrual cycle or the use of hormonal contraception (17, 18).

Figure 5: Illustration of hormonal changes throughout the menstrual cycle.

Nevertheless, it is important to be aware that many athletes experience that this affects their daily training. In a study from 2018 (19), over 50% of a sample of 140 cross-country skiers and biathletes reported that they experienced changes in performance or training quality throughout the menstrual cycle. It was particularly the 1-4 days before and during the period the athletes experienced reduced physical fitness or performance. Recent studies have also shown changes in various recovery markers such as sleep quality, resting heart rate, and "readiness to train" throughout the cycle (20). Here, it appears that athletes who experience more symptoms (pain, reduced sleep quality, and/or heavy bleeding) also have the greatest negative changes in recovery and performance parameters.

Our experience is that there are significant individual differences. Some athletes are almost "non-functional" in certain phases, while others win competitions and set personal records at any point in the cycle. It's about knowing the athlete and having a relationship that allows you to get to know this part of the athlete. Some athletes use conscious strategies regarding the periodization of training load and carbohydrate intake. Here are examples of adaptations that are made:

Specifically, training load is reduced in the last part of the luteal phase (last 4-5 days) by ~15-20% until bleeding. During this phase, the toughest high-intensity sessions, strength sessions, and low-intensity sessions (e.g., 3-hour runs or skating) are avoided.

In the late follicular phase (days 3-7 before ovulation), several athletes have good experiences with increasing the training load and both high-intensity sessions and/or heavy strength training, seem to cost less during this phase.

In addition, some athletes increase their carbohydrate intake by ~20% during the luteal phase.

Hormonal contraception can be divided into two main groups: combined and progestin-only. Combined hormonal contraceptives (oral contraception, vaginal ring or patch) contain both synthetic estrogen and progestin, while progestin-only preparations (mini-pills, IUD, injection, and implant) contain only synthetic progestin. A survey from 2020 (21) showed that in a sample of Norwegian cross-country skiers and biathletes, 33% used IUD’s, 18% implants, 13% mini-pills, 35% combined oral contraception, and 1% patch. Athletes reported that the main reasons for using hormonal contraception (beyond avoiding pregnancy) were the reduction of pain, less bleeding, and/or more control over the bleeding periods. Unfortunately, since most of the research in this area is conducted on oral contraceptives, we know little about how the other types of contraception affect performance and training adaptations. Therefore, the recommendation from research is an individual approach with a focus on the athlete's overall situation.

Our experience is that it is beneficial to have an open and natural dialogue around the menstrual cycle and/or hormonal contraception. Since we still have more male coaches, it is probably extra important to normalize the discussion around these issues. Even though taboos around these topics have been broken down in recent years, there are still many coaches who are afraid of the issues and are more concerned with being cautious than initiating a discussion that could be misunderstood. We believe that more openness and increased knowledge will contribute to more exchanges of experiences, leading to increased well-being, and training quality, and that the athletes more easily can seek medical expertise. It is also important to respect that some athletes are more open and willing to discuss, while others feel that it is too personal. This means that it is important to clarify with athletes what it is okay to talk about and how it should be discussed. Regarding hormonal contraception, we believe that better guidelines specific to athletes should be developed. Coaches should make athletes aware that they should seek advice from a doctor, or gynecologist, with sufficient relevant knowledge related to elite sports. Our experience is that there can be a significant gap between advice from general practitioners to doctors with elite sports experience.

Relative Energy Deficiency in Sports (RED-S)

Relative Energy Deficiency in Sports (RED-S) (22) is common in endurance sports such as cross-country skiing and simply involves conscious or unconscious intake of too little energy relative to expenditure. The incidence of RED-S is higher among female athletes, and the negative health effects also manifest themselves more rapidly. RED-S is also the most common cause of menstrual irregularities because the production of estrogen and progesterone is suppressed with insufficient energy intake. If this continues over time, athletes will experience reduced bone health and an increased risk of stress fractures, thus not being able to tolerate the increased training load necessary for performance development. Sufficient intake of energy in total, also including enough carbohydrates, both throughout the day and in connection with training, is therefore crucial to maintain good health, optimal training adaptations, rapid recovery, and performance for all athletes.

Note! The menstrual cycle is an important health parameter, and the absence of menstruation over three consecutive cycles should always be followed up by a doctor or gynecologist. It is important to be aware that having menstrual bleeding with the use of hormonal contraception cannot be used as an indication that the body is in energy balance.

The importance of energy balance to achieve training adaptations is something we are very conscious of in Team Aker Dæhlie. The goal for everyone (both women and men) is an intake of 60 grams of carbohydrates per hour during low-intensity training and at least 90 grams per hour during high-intensity training. However, we experience a gender difference when it comes to energy intake between male and female athletes, and more female athletes are afraid of eating too much and gain weight. Awareness that there is a higher incidence of eating disorders in endurance sports such as cross-country skiing is important. We believe that openness, education, and clear attitudes regarding long-term health and sustainability in the training process, are crucial for preventing eating disorders.

Our clear experience is that athletes who, over time, consume too little energy and/or carbohydrates experience negative performance development over an extended period. This is also confirmed by studies, which show a close connection between RED-S and the development of overtraining syndrome (23). We see that athletes in energy balance adapt better to training, the recovery time seems to be shorter, and, not least, the mood and general well-being are better!

In a recent letter to the Norwegian skiing federation, five young female cross-country skiers spoke out against the one-sided use of terrain profiles that favor light athletes. We support awareness in the use of competition length and terrain, especially at the regional and national levels, and above all, that young female skiers get the opportunity to become engaged in developing the sport!

Long-term Performance Development

Becoming a top athlete in endurance sports takes time, and there are many examples of female athletes who "peak" in their 30s. The development of FIS points for Astrid Øyre Slind is presented below. Although she developed rapidly as a young senior, she undoubtedly had her best season when she was 35 years old. Therese Johaug, Marit Bjørgen, and Anne Kjersti Kalvå are also skiers who have been at their best in their 30s.

Figure 6: Development of FIS points for Astrid Øyre Slind.

An interesting question is whether women need more time to reach their potential in endurance sports compared to men. An analysis from athletics (24) indicated a higher age for peak performance in both middle- and long-distance running for women compared to men. The same was not found for the development of FIS points in cross-country skiers (25), but there is uncertainty in these data as more women quit significantly earlier than men.

One possible explanation for why women may need more time to reach their potential is that they are somewhat set back by the natural bodily changes during and after puberty. Studies of Swedish cross-country skiers (26) have shown a connection between the development of body composition (increased muscle mass and reduced fat mass) and performance progress in female cross-country skiers, while the same was not reported for male skiers. It can be assumed that female athletes need more time and more years of training both to increase their physiological capacity and their optimal body composition for performance. Here, it is extremely important that coaches have the sufficient knowledge to guide athletes so that this is done in a healthy and sustainable manner.

As shown in Figure 6, the participation rate of women falls from about 40% to 30% from the youth age (15-16 years) to senior age. Encouraging more female athletes to continue with cross-country skiing, thereby increasing the opportunity for more to realize their potential, is therefore an important area for improvement in the sport. The sport needs to find the right progression in training during the transition from junior to senior age and create more inspiring and attractive environments for female athletes. If we look at the number of women on national teams (including elite, recruit, junior, and regional teams), women have been systematically discriminated against with fewer places on teams over a long time period (27). This is reflected in the lower female participation rate in both traditional cross-country skiing and Ski Classics. Another question is whether we are good enough at involving, giving responsibility, and ownership of the development process to the same extent for women and men. Marit Breivik, one of the few female coaches at the elite level in Norway, is known for player involvement as her success factor as a coach. A crucial factor in Marit Bjørgen's return from underperformance, which brought her back to a sustainable world-class level, was taking full ownership of her training process (28). An important effect of increased focus on better support for women will likely be that more women also remain in the sports as coaches, leaders or support staff after their own athletic careers come to an end.

Figure 7: Percentage of women in participation from Mainland Championships to Senior NM (season 2022/2023).

Mother and Elite Athlete

Having children during a career naturally imposes different demands on a female than a male athlete. Several cross-country skiers have shown that it is possible to come back and perform at a world-class level after becoming a mother (29), yet relatively few choose this path. The potential to encourage more athletes to continue is present, but it is essential to identify the mechanisms that can make this an attractive option. In a recent study (30), 13 Norwegian and Swedish cross-country skiers were interviewed about having children during their careers. Analysis of the interviews revealed that athletes mainly experienced four main challenges.

The dilemma of being at the peak of their career just when the biological clock implies that they also must consider having children.

Uncertainty about how much training is possible to conduct during pregnancy safely and responsibly, and how much pregnancy will affect the performance.

How much support they would receive from their team, sponsors, or the ski federation during and after pregnancy?

If it is possible to combine being a top athlete and a good mother at the same time.

These four points should be used to better tailor support so that more female athletes desire to continue their careers as mothers. It is also conceivable that providing security, such as education and internship/job opportunities during and after the athlete's career, will strengthen the possibility of more athletes choosing to continue their careers longer. In many European countries, the state (military, police, etc.) is an employer that pays salaries throughout the sports career and offers a job or education after the career ends. Could solutions like this encourage more women to pursue a longer career? This is something that the sport should investigate further, in close dialogue with female athletes.

Female Coaches

The Norwegian elite sports model is praised worldwide. However, children and young athletes are socialized into sports dominated by male coaches and leaders. As shown in Figure 7, there is a very low proportion of female coaches at various levels in Norwegian cross-country skiing. In cross-country skiing, there is also a large majority of male waxers, leaders, support staff, and sports journalists, making the gender imbalance even more visible at the competition arena.

Figure 8: The number of female coaches in Norwegian cross-country skiing

An often-cited argument for increasing the proportion of female coaches is that they have more relevant knowledge about the female body and can therefore contribute with perspectives and experiences crucial for the development of female athletes. We believe that this should not be the primary argument for increasing the proportion of female coaches, but that coaching teams and support staff with greater diversity in gender, and ethnicity, in general, make better decisions (31). The reasons for this are that diverse teams more often avoid group thinking, where everyone agrees with each other. Additionally, they handle facts more carefully because they must consider perspectives from people who think differently than they do. Groups with significant diversity are often more innovative as problems/challenges are seen/solved in new ways. Based on this, coaching teams consisting of both male and female coaches could contribute to a better and more holistic development of both female and male cross-country skiers.

So why not just do the right thing and hire more women? The challenge is that fewer women want to choose a coaching career at the elite level. There are undoubtedly several reasons for this, but regardless, the challenge must be taken seriously by the entire sports community. One likely reason is the male dominance at all levels. Unfortunately, it is a fact that it is easier for men to recruit men. Team Aker Dæhlie currently has only one female coach. Like everyone else, we must find good solutions to recruit more female coaches. We do not have a definitive answer to what the right strategy is, but we believe it is essential to look at the coaching profession and how we can organize it to make it more attractive to women. We have consciously chosen to have gender balance in our board to shape good strategies for the future.

We work for and recommend the following actions for equal opportunities in cross-country skiing:

1. Get more female athletes to continue longer

Individual adjustments in the training loads tailored to the physiological development.

Patience at all levels – it's okay to train and pursue an athletic career even if you're not at a high-performance level yet!

Better adaptation of training in the transition from junior to senior.

Involve and motivate athletes to take ownership of the development process.

Aim for an equal number of spots for women and men on various teams.

Explore possibilities for mixed relays and team competitions to strengthen cooperation across genders and at the Olympic/Paralympic Games.

A broader range of competition lengths and terrains at the regional and national levels.

Increase knowledge about female physiology.

Inform and facilitate education, jobs, and internships during and after the career.

Provide security for athletes who want to have children during their careers.

Actively work to get more media attention for female athletes (build more female role models).

2. More female leaders, coaches, and wax technicians

Analyze why there are so few women choosing a career in sports.

Inform, facilitate, include, and motivate women who want to become leaders, coaches, or wax technicians.

Actively encourage women to apply for all positions available within the world of sport.

Adjust conditions to make jobs more attractive to women.

Increase understanding of why gender balance is essential – it improves performance!

3. More research on women

Analyze and identify reasons for less research on women.

Financial support that encourages research on female athletes.

Encourage researchers to include female participants in studies.

Written by Guro Strøm Solli together with Team AKER Dæhlie; Trond Nystad, Knut Nystad, Jostein Vinjerui, Hans Kristian Stadheim, Chris Jespersen and Kari Vikhagen Gjeitnes.

References

FN-Sambandet. Likestilling - Indeks for skjevfordeling mellom kjønnene https://www.fn.no/Statistikk/gii-likestilling2023 [

Tombra F. Kvinnene knuser Klæbo & co. i popularitet – Kalvå sovna under VM-renn. NRK. 2023.

Bucher Sandbakk S, Tønnessen E, Haugen T, Sandbakk Ø. Training and Coaching of Female vs. Male Endurance Athletes on their Road to Gold. Perceptions among Successful Elite Athlete Coaches. Deutsche Zeitschrift für Sportmedizin. 2022;Volume 73(No. 7):251-8.

Sandbakk Ø, Solli GS, Holmberg HC. Sex Differences in World-Record Performance: The Influence of Sport Discipline and Competition Duration. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2018;13(1):2-8.

Bolger CM, Kocbach J, Hegge AM, Sandbakk O. Speed and heart-rate profiles in skating and classical cross-country skiing competitions. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2015;10(7):873-80.

Solli GS, Staff HC, SAndbakk Ø. Utholdenhetstrening for kvinnelige utøvere. Den kvinnelige idrettsutøveren. Fagbokforlaget2023.

Solli GS, Kocbach J, Seeberg TM, Tjønnås J, Rindal OMH, Haugnes P, et al. Sex-based differences in speed, sub-technique selection, and kinematic patterns during low- and high-intensity training for classical cross-country skiing. PLoS One. 2018;13(11):e0207195.

McGawley K, Juudas E, Kazior Z, Ström K, Blomstrand E, Hansson O, Holmberg H-C. No Additional Benefits of Block- Over Evenly-Distributed High-Intensity Interval Training within a Polarized Microcycle. Frontiers in Physiology. 2017;8.

Raberin A, Burtscher J, Citherlet T, Manferdelli G, Krumm B, Bourdillon N, et al. Women at Altitude: Sex-Related Physiological Responses to Exercise in Hypoxia. Sports Medicine. 2023.

Walther J, Haugen T, Solli GS, Tønnessen E, Sandbakk Ø. From juniors to seniors: changes in training characteristics and aerobic power in 17 world-class cross-country skiers. Frontiers in Physiology. 2023;14.

Janssen I, Heymsfield SB, Wang ZM, Ross R. Skeletal muscle mass and distribution in 468 men and women aged 18-88 yr. Journal of Applied Physiology. 2000;89(1):81-8.

Solli GS, Kocbach J, Sandbakk BS, Haugnes P, Losnegard T, Sandbakk Ø. Sex-based differences in sub-technique selection during an international classical cross-country skiing competition PLoS One. 2020.

Stöggl T, Welde B, Supej M, Zoppirolli C, Rolland CG, Holmberg HC, Pellegrini B. Impact of Incline, Sex and Level of Performance on Kinematics During a Distance Race in Classical Cross-Country Skiing. Journal of sports science & medicine. 2018;17(1):124-33.

Besson T, Macchi R, Rossi J, Morio CYM, Kunimasa Y, Nicol C, et al. Sex Differences in Endurance Running. Sports Med. 2022;52(6):1235-57.

Okholm Kryger K, Wang A, Mehta R, Impellizzeri F, Massey A, Harrison M, et al. Can we evidence-base injury prevention and management in women's football? A scoping review. Res Sports Med. 2023;31(5):687-702.

Fong HB, Powell DW. Greater Breast Support Is Associated With Reduced Oxygen Consumption and Greater Running Economy During a Treadmill Running Task. Frontiers in Sports and Active Living. 2022;4.

Elliott-Sale KJ, McNulty KL, Ansdell P, Goodall S, Hicks KM, Thomas K, et al. The Effects of Oral Contraceptives on Exercise Performance in Women: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2020;50(10):1785-812.

McNulty KL, Elliott-Sale KJ, Dolan E, Swinton PA, Ansdell P, Goodall S, et al. The Effects of Menstrual Cycle Phase on Exercise Performance in Eumenorrheic Women: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sports Med. 2020;50(10):1813-27.

Solli GS, Sandbakk SB, Noordhof DA, Ihalainen JK, Sandbakk Ø. Changes in Self-Reported Physical Fitness, Performance, and Side Effects Across the Phases of the Menstrual Cycle Among Competitive Endurance Athletes. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance. 2020;15(9):1324-33.

De Martin Topranin V, Engseth TP, Hrozanova M, Taylor M, Sandbakk Ø, Noordhof DA. The Influence of Menstrual-Cycle Phase on Measures of Recovery Status in Endurance Athletes: The Female Endurance Athlete Project. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance. 2023;18(11):1296-303.

Engseth TP, Andersson EP, Solli GS, Morseth B, Thomassen TO, Noordhof DA, et al. Prevalence and Self-Perceived Experiences With the Use of Hormonal Contraceptives Among Competitive Female Cross-Country Skiers and Biathletes in Norway: The FENDURA Project. Front Sports Act Living. 2022;4:873222.

Mountjoy M, Ackerman KE, Bailey DM, Burke LM, Constantini N, Hackney AC, et al. 2023 International Olympic Committee’s (IOC) consensus statement on Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (REDs). British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2023;57(17):1073-97.

Stellingwerff T, Heikura IA, Meeusen R, Bermon S, Seiler S, Mountjoy ML, Burke LM. Overtraining Syndrome (OTS) and Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (RED-S): Shared Pathways, Symptoms and Complexities. Sports Med. 2021;51(11):2251-80.

Haugen TA, Solberg PA, Foster C, Morán-Navarro R, Breitschädel F, Hopkins WG. Peak Age and Performance Progression in World-Class Track-and-Field Athletes. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2018;13(9):1122-9.

Walther J, Mulder R, Noordhof DA, Haugen TA, Sandbakk Ø. Peak Age and Relative Performance Progression in International Cross-Country Skiers. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance. 2022;17(1):31-6.

Jones TW, Lindblom HP, Karlsson Ø, Andersson EP, McGawley K. Anthropometric, Physiological, and Performance Developments in Cross-country Skiers. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2021;53(12):2553-64.

Sandbakk Ø. Evaluering av utviklingsmodellen i norsk langrenn. https://www.skiforbundet.no/contentassets/d1093bd24a004d44a725eb8e268dbe21/evaluering-utviklingsmodellen-i-langrenn.pdf; 2022.

Solli GS, Tønnessen E, Sandbakk Ø. The Multidisciplinary Process Leading to Return From Underperformance and Sustainable Success in the World’s Best Cross-Country Skier. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance. 2020;15(5):663-70.

Solli GS, Sandbakk Ø. Training Characteristics During Pregnancy and Postpartum in the World's Most Successful Cross Country Skier. Front Physiol. 2018;9:595.

Bergström M, Sæther SA, Solli GS, McGawley K. Tick-Tock Goes the Biological Clock: Challenges Facing Elite Scandinavian Mother-Athletes. Women in Sport and Physical Activity Journal. 2023:1-9.

Ellemers N, Rink F. Diversity in work groups. Current Opinion in Psychology. 2016;11:49-53.