Working with technique – why is it so difficult?

Have you ever been struggling to pinpoint what is wrong with the technique as the athletes rush by? You can see that the technique is not perfect, but struggle to identify exactly what it is, and to find the correct words to explain what the athlete needs to change? And you as an athlete, have you experienced frustration or become confused when you do not fully understand what the coach is explaining? In this article, we will present our thoughts and experiences regarding how to work with technique. We will also offer some advice that hopefully can help both coaches and athletes collaborate better. Who should read on? The article is suitable for all coaches and athletes who want to improve. If you are already flawless and perfect - stop reading.

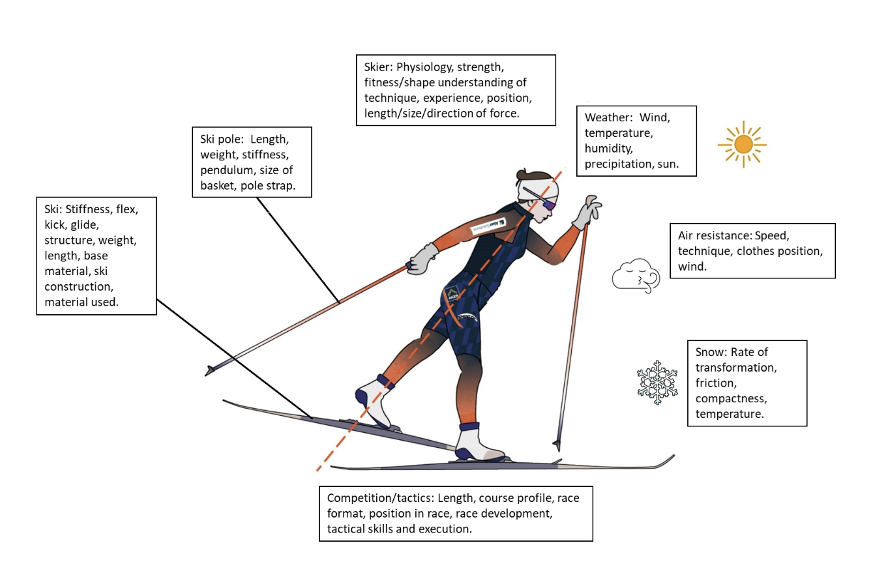

Image 1: Technique is not simple, as there are several internal and external factors that influence the choice of "optimal technique". In fact, it is imperative that the technique changes when the influencing factors change.

To further develop technique, we need to incorporate a holistic strategy and process. This requires that the coach and the athlete have a common understanding of the technique starting point, what the end technique should look like, and what basic principles to work by. Only then is it possible to engage in a shared process leading to improved technique. Although Newton's laws are the same for everyone, technique is something personal, and must be seen in the context of the athlete's unique body composition, physical and motor capacity, mobility, injuries, as well as other strengths and weaknesses. Optimal technique is key to be able to unlock more of the athlete's potential, given the athlete's current physical capacity, strengths and weaknesses. In other words, poor technical skills limit the athlete's ability to become the best version of themselves.

The most important when analyzing and developing technique is not to only focus on errors, but rather to find solutions which will help the athlete develop and understand through trial and error. One technique may be wrong for one type of terrain, but perfect for another. Technique training involves working with technical requirements for a technique/sub-technique, but it can also be working with different gears within a technique/sub-technique (gears = frequency). Finding the cause of technical challenges is detective work. It can often help not to immediately categorically write off the athlete's technical skills as incorrect. Remember that there are many gears in all techniques/sub-techniques, and that different solutions are chosen based on whether the athlete decides to go as economically or as fast as possible. Even if an athlete has near "perfect" technique, new solutions and gears must be tested, trained and incorporated. If an athlete has only one gear in each sub-technique, this will severely limit the performance. A clock with hands that have stopped is precisely correct twice a day, but this does not make the clock a well-functioning precision instrument. Much of the development in cross-country skiing has come as a consequence of curious athletes who have thought outside the box and dared to choose "new" or "wrong" solutions based on the accepted technique norms at the time (e.g. Alsgaard, Klæbo, Koch).

Technical solutions must be "sustainable", which requires different choices to be made based on, for example, the race format, distance, terrain, conditions and "where" one is in a competition. Technique goals can therefore be to:

optimize energy efficiency (VO2) at a given speed and inclination (work economy)

create the greatest possible force in the direction of speed (acceleration costs significantly more energy).

The two points above can be contradictory. One technique costs more energy but is “faster” vs a technique that costs “little VO2“ but does not create as much power/speed. A large toolbox of technical skills is important. The first step is to ensure that the athlete and the coach understand underlying technical principles and master basic skills. This is the foundation for developing good technique. Basic principles of physics and movement theory can help shed light on technical solutions. Newton was not a cross-country skier, but the principles and laws he presented also apply to those of us who want to become better at skiing. The goal is for the athletes to master all aspects of technique, enabling them to choose the correct technical solutions given all internal and external factors influencing the technique choice. This applies both during training sessions and in competitions. To achieve this goal, the coach and the athlete should have a common understanding of 1) basic principles and requirements for good technique, 2) how to adjust technical solutions based on internal and external factors (such as weather, wind, and snow), 3) the educational/pedagogical process to develop, test, learn and implement good technique.

As mentioned in an earlier TAD technique article, working with technique is often challenging. We do not all share the same "tribal language", we do not learn in the same manner, and we communicate and understand differently. This can create frustration over time. To avoid too many repetitions of the technique document, you can read it in its entirety here.

Team Aker Dæhlie has chosen to document what the coaches perceive as optimal technique. It is important to point out that our coaches do not agree 100% on everything. However, we agree that there is no such thing as one "correct technique solution" and that there are many nuances within the various sub-techniques both in classical and skating. Our main philosophy when working with technique is to develop solutions where the athlete can maximize the resistance from the ground, to create an effective and efficient forward propulsion. To maximize the forward velocity, we must utilize the produced force optimally. We aim for optimal body positions and force development. Put in "physics terminology" - we want to optimize the length, amount, and direction of the produced force (poling action and kick with the legs).

This document is not intended to be a recipe that always must be followed to the T. There is not a single movement pattern that is always correct. It is however easier to work together when coaches (and athletes) agree in advance on common words and descriptions for the various technical goals. We hope that the article challenges how you work with technique, and that it creates a broad reflection on "what optimal technical solutions" are. In the end of our discussion, we will summarize what we think are some useful advice regarding technique and the learning process. Hopefully we can help both you as a coach, and you as an athlete, to develop an effective strategy that gives fast results.

Why is technique training so hard? Athletes often struggle to change their technique despite clear and frequent feedback. Coaches struggle to agree on what the technique challenges (and solutions) are, even when they stand side by side looking at the same athlete. What is the problem, and how should we work together to create continuous development through a shared understanding and curiosity? As previously mentioned, a coach's task is not only to find faults with an athlete's technique, but rather to find solutions that enable the athlete to independently solve the technical challenges better. The coach must communicate in a simple and effective manner tailored to each individual athlete’s needs.

Working with technique is a process that takes time. We recommend that the coach and the athlete collaborate to make a plan for how to work on developing technical skills. Below is a suggestion.

Analyze where the athlete is today (which skills are mastered and which need to be improved).

Set goals – what do you want to achieve and when.

Do a GAP analysis (Assess the current situation and the goal(s) to be achieved within a given time period: What tasks must be addressed to achieve the goals? Technique is dependent on physical fitness and strength, i.e. "normal" training can be part of the plan to achieve technique goals).

Agree on a common "technique language" and a process for how to develop the technique.

Plan for how and when you will practice together and alone? What technical aids do you have access to? GPS, video, treadmill etc.).

Use each session as an opportunity to develop, test and learn – remember to document the process and what you learned.

Test if the process has worked (GPS, treadmill tests, test races etc.).

Based on the "tests", evaluate and adjust the plan to ensure that it leads to continuous improvements and reaching the set goals.

We are often confronted with coaches and athletes who are convinced of the superiority and effectiveness of their "own" technical solutions. What exactly is a perfect technique, and what is our judgement based on? Currently we do not have good measuring devices to "quantify" what good technique is. The closest we get is a treadmill for roller skis. It gives instant feedback – if we do something correctly, we move closer to the front, and if we execute poorly, we get pushed back on the treadmill. We are probably all guilty of trying to shape the technique truths based on what the best athletes do. The best athletes ski extremely well (and fast), but even the best athletes are not satisfied with all aspects of their skiing, hence they put in significant of training hours to improve their technique. No one is (should be) satisfied with every aspect of their own technique. To be an elite athlete you must train a lot. If you practice a lot on something that is sub optimal, you will still be able to reach a high level, but you will probably miss out on becoming the best version of yourself. An old Norwegian saying goes something like this: “If you think you are finished learning, then you have not learned much, but you are finished” – we therefore must approach the learning of technique as a continuous and endless journey. The development and mastery of technique are never completed, as both internal parameters (shape, strength, physical properties, etc.) and external parameters (weather, trails, competition format and equipment) are constantly changing. Given that we have proudly watched Viktor Hovland and Team Europe defeat the Americans in the Ryder Cup, it is appropriate to use some examples from the world of golf. Golf is a technically demanding sport where technique “truths” and thoughts have existed since the beginning of time. Descriptions of how one should execute the perfect golf swing that sent the ball with a desired ball trajectory toward the flag, were established truths for several years. These “truths” stood unchallenged until the sport discovered technical tools (e.g. Trackman) that could measure what actually happened during a golf swing. Opinions were replaced with facts, and new truths were established. The advance of technological innovations forced old golf gurus across the golf world to alter their own opinions and rewrite the technique bible. Technology increased the understanding of the correct golf technique and led to new approaches and solutions in pursuit of lower scores. Even Hovland has changed coaches to become better (or perhaps preferably to avoid mistakes). The new coach is best known as the "Trackman Maestro" — he analyzes what Hovland should prioritize based on facts. Hovland said it best himself in an interview — "the golf ball does not know if you have slept or eaten well. It's physics, it's math."

Image 2: Using different sub-techniques is important, and these often overlap.

Athletes will learn to use technique as a "tool" to perform better if they first learn to work with technique in a conscious manner. Athletes who are “on” can implement targeted technique training and more easily improve. Our opinion is that optimal technique is about perfect implementation of the technique itself AND the ability to choose correct technical solutions based on internal and external factors. The goal of any technique is simply to utilize the resistance from the ground to create an efficient and effective forward propulsion. In order to increase the understanding and the learning, the athlete and the coach must therefore consciously and accurately work on technical improvements and experiment with different solutions under different conditions. This will lead to continuous improvements.

To make the process of technique development as efficient and effective as possible, it is important for the athlete to independently work on technique during every training session. It does not make sense to only focus on technique when a coach or a video camera is present. In a perfect world, the athlete should work on technique every minute of every workout. This is of course not always feasible, but it is a great goal. In order to work consciously with technique, we need to practice being focused and present. We see many athletes cruising around on skis while listening to loud music, or who are deeply engaged in "chit-chat and gossip" while training. This is of course of great value for the social aspect and “well-being” of an athlete, but it is not optimal for the process of developing great technique (having said that, we need both - fortunately it is not either/or). Focus can be trained! Choose a few sessions where the athlete should work on technique focus - alone and with training partners. Set an alarm on your heart rate monitor every 10 minutes. The signal is a reminder to once again focus on technique. At first, it's hard to stay focused, but with a little practice, you quickly improve. Focusing on technical tasks leads to positive development that for most people is incredibly rewarding. Many athletes are surprised how quickly time passes by when they have meaningful tasks to work with. The bonus is the feeling of mastery and constant improvements.

The athlete's and coach's knowledge and understanding of good technique serves as the foundation for effective and efficient learning. Spend time reading, watching videos and discussing different technique solutions to develop a shared understanding of technique. A better basic understanding allows for effective technique development alone and in a group. It is also important to be smart (and brave) enough to challenge established truths. The current process for developing good technique, the language, and the definitions of technique may not be 100% correct. The interaction between athlete and coach is important. In order for the process to be as good as possible, it is wise that you spend time to establish a common language. This will ensure a good and effective dialog where everyone understands the same, regardless of whether you agree with each other or not. A famous Norwegian alpine coach (Finn Aamodt) summed this up well: “What we agree on brings us together, but what we disagree on, brings us forward”. This is also true when it comes to technique.

When working with technique, there are two important perspectives – the athlete perspective and the coach perspective. We will briefly give some advice that strengthens and enables cooperation between a coach and an athlete.

The Coach Perspective:

Many athletes expect the coach to be able to immediately identify "flaws" and provide easy universal solutions to technical challenges. This has probably led some coaches to evolve into "experts" who are willing to give instant and surgically precise feedback on everything to everyone. This, in turn, has led to many (other) coaches being intimidated and afraid to get involved in the technique discussion, as they do not feel adequately qualified to have an opinion. For those who feel insecure (and there are many of us), you may want to understand the "Dunning Kruger effect". Read about this on the internet and accept that everyone needs time and experience to develop a “true” understanding of technique, and an effective communication method that ensures athlete understanding. Remember #1 that communication is difficult. Remember #2 – if you want to be good at something, you must practice for a long time. Fortunately, people are different and learn in different manners. Some need metaphors to understand, others need to have an "image" in their head, while others need to feel the “correct" movement. Experiment with words, expressions, images and a "feeling" when discussing technique.

How do we identify technical challenges? How should we prioritize our work with the identified challenges? As coaches, we want to work with the most important issues before we solve smaller ones. If you solve the bigger challenges first, oftentimes the smaller ones improve or disappear. Do not give the athlete too many tasks to work on – 1 to 2 tasks per technique is more than enough! The order in which we work to “diagnose and find the right treatment” is:

Balance in desired position and weight transfer.

Vertical weight transfer in a balanced position.

Coordinated push/force in the desired direction.

Balance in the desired position and weight transfer.

We first check if the athlete is in balance in the desired position. Is nose/knee/toe aligned? If the athlete does not have sufficient balance, we prioritize this challenge first. Good balance is a pre-requisite before proceeding to the next technique step. The desired position is, for example, high position, forward fall/lean in the body, deep position, athletic position. More on this in a separate point.

Good exercises are:

Squats on one leg

Imitation jumps to simulate ski technique – preferably with control jumps to check that balance is present before jumping to the other side.

Glide for a long time on one ski.

Ski without poles, or complete 5 cycles with poles and 5 without poles.

The "super V2" exercise: The athlete glides on a ski and execute two pole strokes per leg kick.

Vertical weight transfer:

Vertical weight transfer means that the athlete can execute a "squat" (on one and two legs) without losing balance. The athlete must be able to create a sharp angle in the ankle and knee by lowering the weight and without losing balance. Vertical weight transfer enables a strong leg kick/double pole motion, which gives the potential to create force in the right direction.

Good exercises are:

Squats with jumps. Preferably with control jumps on each side to show balance.

Box exercises where you push yourself up onto a box using coordinated push/arm pendulum.

Imitation jumps that simulate ski technique. Preferably with control jumps that show good balance.

Double compression squats and jumps

Coordinated push/force in the desired direction.

When the athlete masters steps 1 and 2, one must ensure that the upper body and the legs work harmoniously and synchronously creating force in the desired (same) direction. If the athlete manages this, it will provide maximum power and speed. The force/kick creates the horizontal weight transfer in (hopefully) the desired direction. In some cases, it may be that the athlete manages to create force and is coordinated but is unable to direct the force in the right direction, or is unable to complete the movements. If this is the case, the exercises must be adapted.

Good exercises are:

Contrast exercises – coordinated arm swing vs. uncoordinated arm swing, long push vs short push

Kick off in an imaginary direction on the clock (where 12 is straight ahead, 3 is 90 degrees out to the right and 9 is 90 degrees out to the left). Varying the direction of the kick to learn what works best. This can also be done as control jumps without skis in all techniques.

Right position:

In order to find the right positions and to find solutions which maximizes the most power/speed and/or is most economical/sustainable, one should include the athlete and find exercises where the athlete can learn and feel. This can be filming, GPS, contrast exercises, time spent on a lap, pulse, lactate, etc. Video is a good tool as the athlete quickly can watch if the "self-perceived image" matches the video image. Often skiers are surprised to observe that the video image is significantly different than the internal (self) image of how they ski. Technique videos are easy to make as everyone has a camera available on their mobile phone, and you can review the technique in slow motion at your own leisure. The downside is that video analysis takes a long time (especially with a large group of athletes), and often reviews of videos take place after training (not timely). When analyzing technique videos, you may want to start with a review of how the upper body works, and then look at the legs. In our experience, the legs often "follow" the rhythm of the upper body.

Another method is the use of contrast exercises where the athlete switches back and forth from one extreme position to another extreme position. Through such exercises, one can empirically test different solutions and quickly agree on what is the fastest and/or cheapest technique. Examples are: long/straight arms vs short/bent arms, pole tips far back vs far forward, weight on toe ball vs on heel, come up on the toes in double pole vs keeping the weight on the heel, chicken wings vs elbows along the body, small vertical drop vs. large vertical drop, use of core/stomach (crunch) vs more arm use, high frequency vs lower frequency, etc. If the athlete masters the extreme positions, it will be easier to identify the optimal solution located somewhere between the two positions. As a coach, it is important to observe how the athlete responds to the exercises. Is the athlete able to challenge themselves? Can they tell the difference? Our experience is that most people respond well to such exercises and that they themselves can identify advantages/disadvantages with each solution. When the coach and the athlete agree on the best position, it is easier to conclude that the "truth" lies closer to one extreme position than the other. By using a standard lap (or a treadmill), time, pulse (possibly lactate) – it is possible to test different movement patterns, technical solutions, gears, and strategies. The extremes can also be used as reference points if the athlete needs to "calibrate" the technique along the way.

Each coach has their own way of observing, analyzing, and working with technique. To increase own understanding, it is important that the coach also tries out different solutions. This experience often leads to improved communication about technique. It is very educational and valuable if the coach ski together with the athletes.

The Athlete perspective

Athletes must take ownership of the development of their own technique. "If it is worth doing, it is worth doing it right!". Learning and mastery of technique depend on curiosity, focus, experimentation, and repetition. The goal is that the athlete train with perfect technique as often as possible, to ensure that the technique is automated. The athlete should be able to make very clear and conscious decisions about which techniques and gears are most optimal, given the external and internal factors. A conscious choice to not think about technique is okay sometimes, but this should be the exception rather than the rule. As an athlete, you should ask yourself some important questions: Are you curious enough about finding new and better solutions? How can you motivate the coach and the team to share your curiosity? What should a coach expect from you as an athlete? What is your responsibility as an athlete? Is your understanding of technique adequate? Does your own image of your technique match the reality?

It is not easy to receive "criticism" of technique, as technique is something personal. Sometimes it helps to consider that it is equally challenging to "criticize" someone. Just know that if someone takes the time to say something to you about your technique, they have good intentions and wish to help. Your responsibility as an athlete is to listen, try, discuss and give feedback. When someone invest their time to give you advice, then you owe it to them to listen (and sometimes you should also consider to say thank you 😊). A coach gives feedback and advice with the intent of helping you develop as a person and as an athlete. If there's something you do not understand, or do not agree with, then ask and discuss. Not bothering to try new concepts or even worse “sabotaging” technique advice will not lead to positive development. Always give technical advice a chance - worst case you find a technique that is not advantageous and can move on to test a different solution. Objective data, such as time used on a lap, heartrate and lactate can be used to confirm effective technical solutions. Working with technique is teamwork and requires trust. Together you can learn from each other. The goal is for you to become so independent that you can work on the development of your technique on your own. This requires that you take ownership of your own development. A good starting point is to have an open mind and being curios. Share your experiences with your coach and keep exploring/developing. This will help both of you to build your skill sets and to develop in the right direction. Remember that you are responsible to develop your own skills and those of your coach.

As an athlete, you need to know that giving technique advice is challenging. All athletes are different and have different areas where they can, and should, improve. What is right for you may be wrong for someone else. When a coach says something to one person and something else to you, it can be confusing. Remember the advice is often given based on each athlete’s individual and unique technical challenges at that time. A coach depends on a good dialogue with the athlete. Each athlete is unique and "decodes" the coach's messages differently. This requires that we as coaches often must be creative and give different "visual clues" to each and every athlete.

It is important to agree that the goal is not to develop a training technique and a competition technique. The right technique should be possible to execute regardless of intensity. This applies to both "easy" and "fast" techniques. Remember that 80% of the training sessions and 90% of the training time is performed at low intensity. For coaches, it's incomprehensible that athletes chose not to use this time to practice correct technique/gears. We often hear that it is impossible to ski slowly with a great technique. It is imperative to focus on your/good technique during all training sessions IF you want to train to improve. If you do not want to improve, you do not need to have a constant focus on technique (but please tell the coach so that (s)he can give more attention to someone with a stronger desire to become better). You often do not need to find more time to improve, the most important thing is to use the time you already invest in your training more effectively. Doing the “little things” (which can make a big difference), correctly does not require more time. "Little things" are, for example, technique, intensity, nutrition, hydration, etc.

Coaches must explain technique goals and challenge the athletes to think of good technical solutions during every session. You as an athlete must understand (and agree on) these technical goals and be prepared to work continuously to improve. Technique is not something you do to appease the trainer!

A coach must motivate athletes to experiment with technique. What motivates you as an athlete? Have you talked with your coach about what motivates you? Good and motivating exercises are contrast training, contrast exercises together with other athletes, imitation exercises etc.

Coaches do not have to be adamant about technique – we can explain what we think is better and challenge the athlete to feel the difference by using, for example, contrast training. In the end the athlete must/should choose the best solution. As an athlete, you must be prepared to “feel” the difference between two different technical solutions and explain this difference in your own words. Great solutions are found through trial and error, dialogue, and discussion. Work with one to two tasks at a time. Improvements require patience and continuity.

A good piece of advice for all athletes is to try to coach someone else. When you as an athlete step into the coaching role, you will experience the challenges of identifying technical issues and how to communicate changes/solutions. The advantage is that you gain keen insights about technique and oftentimes discover new approaches that will also assist you in your own development. This applies both while out on skis and/or when analyzing video/GPS data.

Technique is constantly evolving and changing. Currently we do not have adequate technical tools which can guide and give us the perfect "recipe" for what is the optimal technique and how to best implement it. We therefore need to experiment to find optimal solutions. The coach and the athlete have a joint responsibility for the development of the technique. This requires both parties to practice together as often as possible. The development process depends on a good and shared understanding, as well as an on-going curiosity to experiment with different choices. Technique is not static. Weather, wind, snow, as well as several other factors, require us to master several technical solutions. We hope that this article can stimulate a discussion on how to best approach the technique work. Good technique is the key to unlock your physical potential and become the best version of yourself. Technique does not have to be challenging for neither the coach nor the athlete, but it requires good dialogue, cooperation, ownership, and curiosity.

Written by the team of coaches in Team AKER Dæhlie v/Trond Nystad, Knut Nystad, Jostein Vinjerui, Hans Kristian Stadheim, Chris Jespersen and Kari Vikhagen Gjeitnes